As summer approaches and lockdown eases, Sydneysiders find themselves face-to-beak with the notorious Australian white ibis – often derided as ‘bin-chickens’; but there’s more to this protected native species than meets the eye.

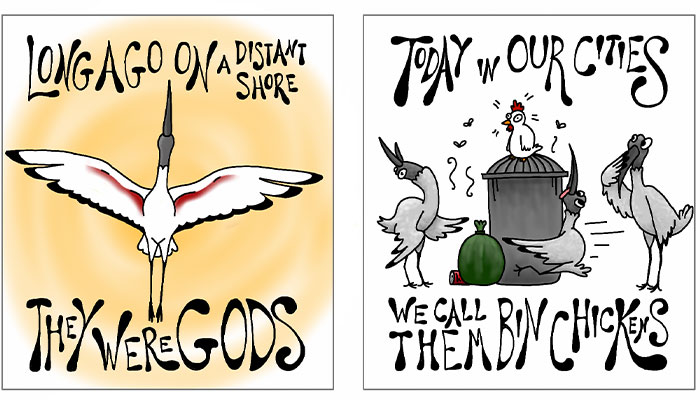

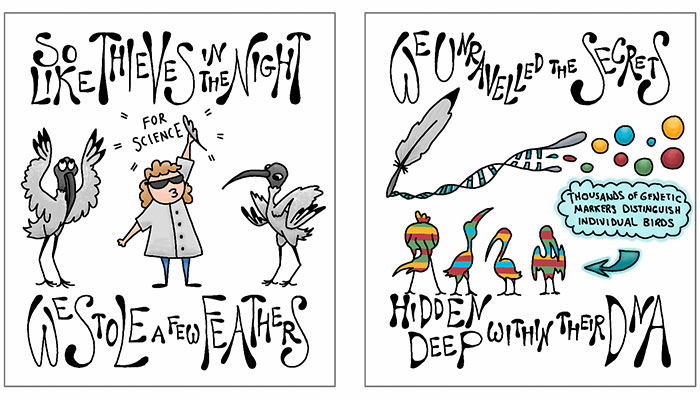

New perspectives: Cartoon illustrations by PhD candidate Skye Davis tell the story (from top to bottom) of the Macquarie University research findings into ibis populations.

Public parks, playgrounds and other urban environs are now favourite haunts for these much-maligned birds – so most people are surprised to hear that ibis populations across the inland wetlands of the Murray-Darling basin are declining.

Associate Professor Adam Stow, a biologist who heads up Macquarie’s Conservation Genetics laboratory, and Dr Kate Brandis from University of NSW recently published new research on ibis populations with PhD student Skye Davis in the Journal of Conservation Genetics.

The team uncovered good news: enough genetic diversity exists across now widely dispersed ibis populations to ensure ongoing genetic health for struggling inland ibis groups.

Inland ibis are beautiful, elegant white birds that look and act nothing like their grubby and cheeky city cousins.

Davis compared genetic samples from the moulted feathers of the white ibis who lived in Australia’s inland waterways with urban ibis – and was surprised to find no detectable genetic differences.

The apparent difference in appearance between grotty city-dwellers and glossy wetlands-dwellers was all down to bad bird behaviour.

“Inland ibis are beautiful, elegant white birds that look and act nothing like their grubby and cheeky city cousins,” says Davis, adding that inland-dwelling ibis are unused to people and can abandon their nests when disturbed by humans.

The native bird we love to hate

The Australian white ibis is part of the same family as the sacred ibis, native to the Nile valley and worshipped by ancient Egyptians as the moon-god Thoth.

Interestingly, the sacred and Australian white ibis were thought to be the same species until classified them apart.

But despite their royal antecedents, Australia’s ibis are often reviled by city-dwellers who only see them scavenging leftovers in bins, or stealing food from picnics, leaving the birds scruffy and dirty, Davis says.

Plentiful urban food sources have led to an unnatural rise in ibis populations in urban parks, where excrement from nesting and roosting ibis can foul ponds and lakes.

“A lot of people are genuinely scared of them, maybe because of their long curved beaks,” says Stow, adding that while ibis are generally harmless to humans, they can be intimidating.

City survivors

The shift in ibis populations to urban areas occurred over the past 30 years or so, as their main habitat degraded – and it’s this adaptability that could save them.

Dr Kate Brandis from the UNSW Centre for Ecosystem science, a co-author on the research, says that water resource development, reduced wetland flooding and climate change have impacted inland ibis populations.

“Australia’s inland river systems and wetlands are seriously degraded which has led to the loss of a lot of water birds that play an important ecological role – including the ibis,” says Stow.

The ibis manage inland insect populations, preying on small grubs and locusts – so their loss from inland areas has been troubling, he says.

It wouldn’t surprise me if ibis form little gangs when they raid garbage, they certainly get around some of the attempts to control them.

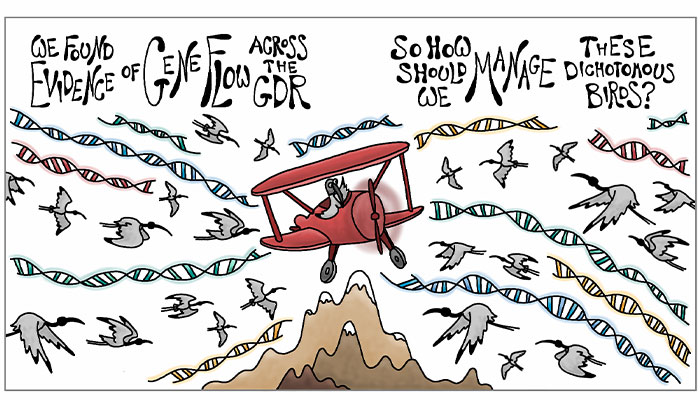

“Our work suggests that there’s intermingling between the inland and coastal ibis,” says Davis.

“That indicates that Australian white ibis are technically one large metapopulation, which is important to know – because we currently have two very different ways of managing ibis between inland and urban habitats, and we should look at this as a whole.”

Ibis urban control programs

The birds’ success in adapting to urban environments has led to various local government ibis control programs involving waste management, egg oiling and pruning trees used in nests – all done under license, as Australian native birds are protected under various state wildlife schemes.

Canterbury-Bankstown Council in NSW that use strategies like ibis-proof bins and licensed contractors to removing nests or oiling eggs to prevent hatching.

Brisbane Council now lists over 17 ibis egg cull locations following a 2019 overpopulation crisis as bird droppings in the lagoon and resulting blue-green algae left an unbearable stench.

Perth’s East Metropolitan Regional Council in 2018 to reduce the bird strike hazard to aircraft at nearby Perth Airport.

“Those localised management efforts are often counterproductive, because while it might temporarily control the birds from that area – they just move somewhere else, and as soon as you stop those management practices, the ibis are likely to come back,” says Davis.

Gangster ibis and the school of hard knocks

Various urban-adapted birds like cockatoos and magpies have been observed teaching each other to raid food sources and open garbage bins – and while there’s no such studies on ibis, Davis says that she notices all kinds of personality traits when observing the birds.

Drawing conclusions: PhD candidate (and illustrator) Skye Davis says localised efforts to manage urban ibis are often counterproductive.

“It wouldn’t surprise me if ibis form little gangs when they raid garbage, they certainly get around some of the attempts to control them,” she says.

Examples include groups of ibis on the Gold Coast which to protect their eggs from council control officers.

But while tree-changing ibis are currently a source of genetic diversity for inland populations, Davis says it will be interesting to see if genetic differences between the two groups on either side of the Great Dividing Range emerge over time.

It’s a disturbing thought: will mutant gangs of ibis eventually emerge to continue terrorising the bins of Sydney?

is an Associate Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences.