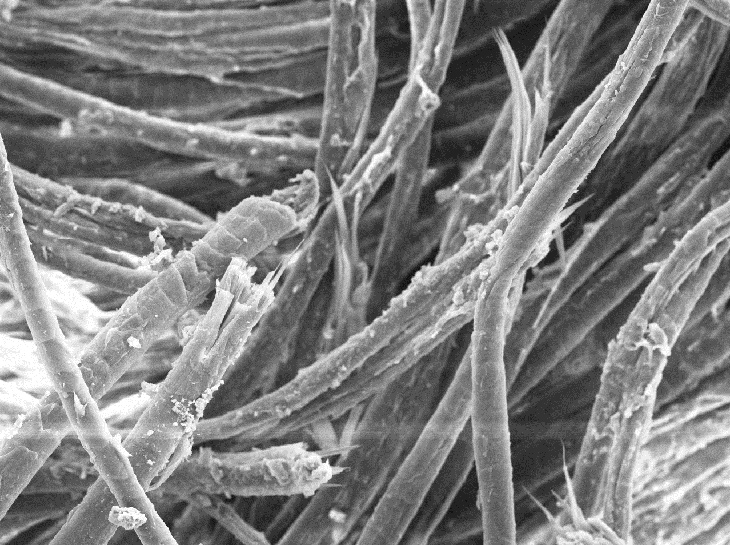

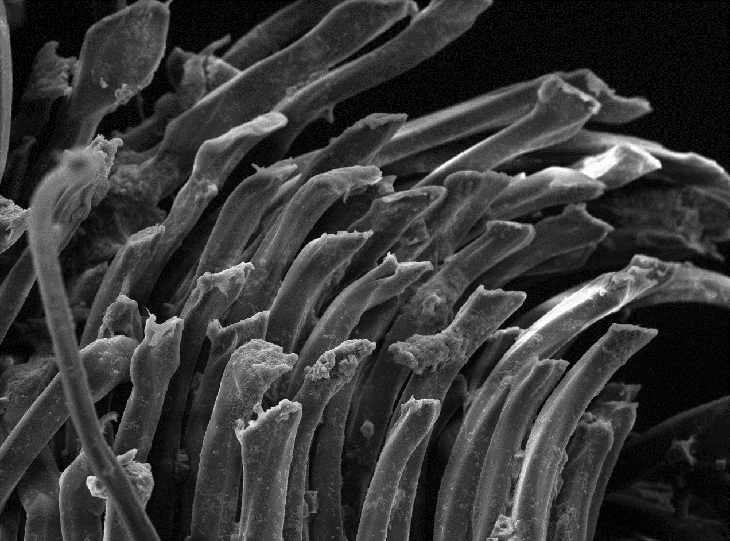

Residues from machine-washable wool (top) and polyester (bottom). The degradation of wool is clear, as is the lack of degradation of the synthetic fibres.

Research funded by AWI has shown that machine-washable wool fibres as well as untreated wool fibres readily biodegrade in the marine environment, in contrast to synthetic fibres that do not. The research found no evidence to support the idea that the polyamide resin used as part of the machine-washable wool treatment forms microplastic pollution.

It is estimated that 0.6-1.7 million tons of microfibres are released into the oceans every year. An important source of this pollution is fibre shedding during the laundering of apparel.

This seemingly ubiquitous contamination of the environment with fibres and fragments from textiles, especially from synthetic fibres, is of growing concern amongst brands and consumers.

Previous studies have already shown that wool biodegrades in the natural marine environment, which is good news for the wool industry and the planet. However, the aim of this new study, undertaken by AgResearch and funded by AWI, was to measure the rate of biodegradation (in the marine environment) of wool relative to competing fibres, and study the residues produced.

“One of the main objectives was also to disprove the idea that machine-washable wool might create a form of microplastic pollution,” said AWI’s Program Manager for Fibre Advocacy and Eco Credentials, Angus Ireland.

“It had been suggested that the commonly used polyamide resin (Hercosett) on machine- washable wool, which prevents the wool felting, might break into fragments as the wool fibre degrades. It was important that this suggestion be examined and refuted scientifically.”

RESEARCH PROCESS

Scientists from AgResearch undertook the study using a method based on an established standard for measuring marine biodegradation. Residues were examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX).

The samples used in the study were sourced from comparable lightweight base-layer fabrics, each made from the six fibre types being studied

- two types of Merino wool: machine washable wool and untreated wool

- viscose rayon, which is made of cellulose derived from plant sources such as wood pulp

- three synthetic fibres: polyester, nylon (a polyamide) and polypropylene.

The fabrics had been deconstructed (shredded) to remove any possible interference from the way the fabrics were structured. Furthermore, the fabrics had been washed repeatedly before testing, to simulate a partial garment lifetime.

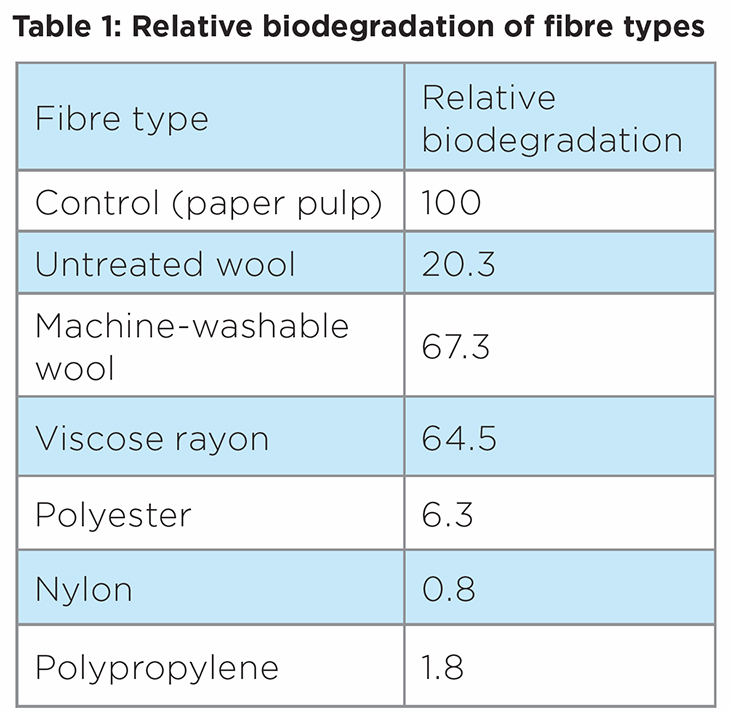

The average biodegradation of three samples for each of the six fibre types was measured relative to a ‘positive control’ (ie a sample known to biodegrade readily). In this study, the positive control was kraft paper pulp.

RESEARCH RESULTS

Table 1 above provides the amount of biodegradation of the six fibre types during the 90-day trial period, expressed relative to the ‘positive control’.

“The study shows that both types of wool biodegrade to a high degree, as does the cellulose-based viscose rayon. Synthetic fibres show little or no biodegradation,” Angus said.

The treatment that makes wool machine- washable (the application of a thin polyamide film to the fibre surfaces), actually caused the wool to biodegrade more rapidly than untreated wool. The scientists believe this is probably because the treatment process removes some of the fibre’s cuticle (its armour plating), rendering it more susceptible to microbial degradation. It is important to note that the polyamide resin used in the machine- wash treatment for wool is very different from common commercial polyamides.

“Significantly, the scientists did not detect any formation of microplastic polyamide fragments resulting from the biodegradation of machine-washable wool,” Angus said.

Based on observations from soil biodegradation, the scientists expect that over a relatively short time wool will biodegrade completely in the marine environment. The rate of biodegradation for untreated wool is likely to increase to be similar to that of machine-washable wool once its cuticle is broken down.

ANOTHER STRING IN WOOL’S BOW

The results of the new study complement previous AWI-funded research into microplastic pollution from textiles, which recommends an increased use of natural non- synthetic materials, such as wool, in global textile markets.

“This is yet another study that helps demonstrate the eco-credentials of natural fibres in a world where there is increasing concern about the effect on the environment of synthetic textiles,” Angus said.

It is part of a larger body of work by AWI towards better accounting for the use phase in Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of apparel.

“Natural fibres such as wool readily biodegrade and consequently don’t amass in the environment. This important difference between natural and synthetic fibres needs to be accounted for in Life Cycle Assessment for the LCA to be credible and scientifically defensible,” Angus added.

This article appeared in the June 2020 edition of AWI’s Beyond the Bale magazine. Reproduction of the article is encouraged, however prior permission must be obtained from the Editor.